= ASTRONAUTICAL EVOLUTION =

Issue 141, 2 September 2018 – 49th Apollo Anniversary Year

| Site home | Chronological index | About AE |

The Religion Question

Why an interest in religion?

Professor Konrad Szocik has an article in a 2017 issue of Spaceflight proposing “an imposed Martian religion as a spur to ethical and socially equitable conduct”. Some responses, mainly critical, were published in a subsequent issue. Professor Szocik’s thesis has also appeared online.

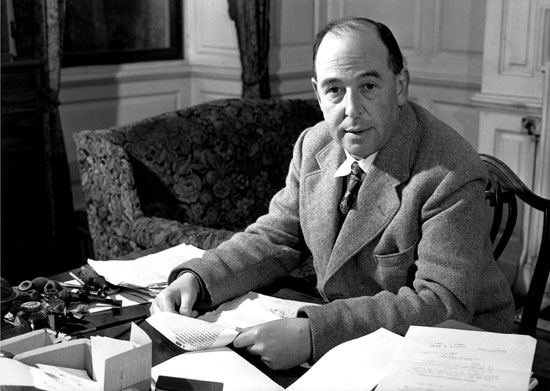

Meanwhile my reading interests have recently been returning to C.S. Lewis, who was quite an influence on me when I was a teenager. I only recently realised that one could visit what used to be his back garden next to his house in the Oxford suburb of Risinghurst – a short bus ride from where I live. This quiet wooded spot is very much like a scene from his fantasy world of Narnia (though to find the real inspiration for that world one must travel to the Carlingford Mountains and the Mountains of Mourne in north-eastern Ireland).

Both grappling with Professor Szocik’s perverse logic, and re-reading Professor Lewis’s inspired fictional worlds, brought me back up against all the arguments for and against Christianity with which I had once wrestled as a hopelessly mixed-up adolescent.

Meanwhile the surge in hardline atheist books and programmes in the past decade or two, responding to the continued stridency of hardline religious sects particularly in the USA and the Middle East, shows that this subject is not going to go away quickly. The implications of continued religious belief for the future of civilised life on Earth as well as on Mars and other points in space need to be thought through.

In order to get some perspective on the problem, I re-read Professor Dawkins’s notorious but certainly entertaining book The God Delusion. It is the central argument of this book which will be the subject of this post.

“Why there is almost certainly no God” – a case of circular logic

Discussing arguments for God’s existence Professor Dawkins writes (p.136):

“There is a much more powerful argument, which does not depend upon subjective argument, and it is the argument from improbability. It really does transport us dramatically away from 50 per cent agnosticism, far towards the extreme of theism in the view of many theists, far towards the extreme of atheism in my view. […] The whole argument turns on the familiar question ‘Who made God?’, which most thinking people discover for themselves. A designer God cannot be used to explain organized complexity because any God capable of designing anything would have to be complex enough to demand the same kind of explanation in his own right. God presents an infinite regress from which he cannot help us to escape. This argument, as I shall show in the next chapter, demonstrates that God, though not technically disprovable, is very very improbable indeed.”

And the next chapter, entitled “Why there is almost certainly no God”, develops this line of reasoning and “comes close to proving that God does not exist”.

It was when I first read this chapter a few years ago that I started thinking of Dawkins as the Professor of the Public Understanding of Circular Logic.

Consider: Dawkins’s assumption is that all complex phenomena arise from simple states subject to natural selection over time. Clearly this works well for terrestrial biology. But is it a universal rule, applicable even to the origin of the cosmological universe? Dawkins is asserting that it is: for him it is a fundamental axiom. Theists are asserting that it is not. The axiom is itself the point at issue.

Dawkins is asserting that all organised complexity, up to and including any supposed divine being, is vastly more likely to appear through an evolutionary process over time than to have always existed. This rejection of even the possibility of an eternal divine being might be described in Dawkins’s own words, but taken from a different context, as “the argument from personal incredulity”. One might put Dawkins’s argument in a nutshell as follows:

- Axiom: an eternal, omnipotent, omniscient divine being cannot exist (due to its intrinsic “improbability”).

- Premise: God is such a being.

- Conclusion: therefore God does not exist.

The logic is trivially true, but irrelevant. The theists are asserting that there exists at least one phenomenon for which the starting axiom is not true. We are therefore not in the realm of logical deduction from agreed premises, but that of observation and evidence, and here the situation is far less clear-cut than Professor Dawkins (or indeed I myself) would wish.

In fact his own words betray him. Dawkins says: “God, though not technically disprovable, is very very improbable indeed.” This from the man who wrote a book entitled Climbing Mount Improbable – his argument that something appears to our eyes extremely improbable, yet can still be true, works both ways. That the complexity and richness of life evolved by natural selection from simple beginnings seems improbable, yet we can see how it may be achieved. That a designer God existed before our universe ever came into being seems “very, very improbable indeed”, yet again it may be true – at least, according to theists it may.

Alternative scenarios

My favoured method of dealing with uncertainty is to construct a range of alternative scenarios. Here, two alternatives to Dawkins’s position leap to mind:

- Firstly, the theists might be right: there may in fact exist one example of organised complexity (God) which has always existed and always will exist, without being subject to change in time.

- Secondly – supposing however that the evolutionary axiom used by Dawkins is correct even when applied to the whole universe – it may still be the case that there exists one example of organised complexity (God) which predates the Big Bang believed to be the origin of our universe, but which evolved through natural selection in some prior universe, and developed to the point where it was able to deliberately create new universes of its own, such as the one we are living in today. There is no need for an infinite regress.

Clearly, neither of these scenarios impact upon the question of biological change. In either scenario biology may still proceed according to natural selection (given the time available, it is hard to see how or why a divine being would prevent natural selection from occurring).

The second scenario would apply in the case where our entire universe is a computer simulation in some higher-order universe, as has sometimes been proposed by more adventurous thinkers, and dramatised in The Matrix.

Given our current ignorance about the hypothesised multiverse (if it exists), the second scenario would in practice be indistinguishable from the first, even though logically distinct. Thus it is not even necessary to determine whether the evolutionary axiom is true when applied on this grand scale.

Thus our only recourse is to observation: do we in fact observe the existence of God, or not?

Searching for God in the 21st century

Clearly, some people think they do sense God’s presence, others think they do not. The theists claim that the atheists are deluded; the atheists return the compliment.

I noticed while reading Professor Lewis that Christianity depends on the existence of a sort of extrasensory perception. This is brought out clearly in his last novel, Till We Have Faces – I say “clearly”, but I didn’t understand it at all when I read it as a young man, and only re-reading it now do I see what Lewis was getting at. Namely, that our minds are so corrupted by sin that we cannot see our true situation in the universe at all, or understand our true motives, hence his conclusion (at the beginning of the final chapter), in the person of his heroine Orual, Queen of Glome: “How can they [the gods] meet us face to face till we have faces?”

It is striking that, whereas Dawkins’s attention tends to be focused outwards, towards the phenomena of the sciences, and his internal mental state is seemingly derived from that, Lewis sees introspection as more fundamental, and the phenomena of physics, biology and so on as being of secondary importance.

These are deep waters, and we’re not going to be able to solve them in this blog post. I want to finish with a practical conclusion for the present.

The two modes of religious practice

Another problem I find with Professor Dawkins’s writings on religion is that he often fails to make a distinction between two modes of religion which are different from one another – though obviously closely related. I think it is critical for clear thinking to keep this distinction in mind:

- Militant religion – the use of a particular branch of religion as a basis for politics, with a veto on lawmaking, a divinely sanctioned justification for violence against unbelievers, and with all the mutual intolerance of competing sects which that entails.

- Devotional religion – the use of religion for private practice, a basis for one’s personal meditations on the nature of life and for personal moral choices within the law.

It is my contention that the attitude evolved in the 18th-century Enlightenment is the key to dealing with religion, namely:

- Militant religion cannot be tolerated in an enlightened political state, because such a state functions best and most humanely when it fosters the creativity of people with a wide variety of philosophical views.

- Devotional religion is an important human right, and freedom of conscience in religious matters must be tolerated and protected by the same enlightened political state.

The fundamental principles are those of mutual tolerance among mutually tolerant points of view, and a practical politics founded on compromise, on give and take among all parties. These arose in the 18th century in response to the hideous cruelties of the religious wars of earlier centuries, particularly between the Catholic and Protestant churches.

With these principles, we have a practical method of organising society without needing to solve imponderable theological questions. Those questions belong to the private, not the public, sphere, and should therefore be discussed in an atmosphere of polite intellectual enquiry, not one of existential fear leading to extremism and violence.

Clearly, Dawkins’s approach is conditioned by the fact that he is responding to political issues such as the fundamentalist Christian movement in the USA which attempts to suppress the teaching of evolutionary biology in schools, or the Middle East conflict, as his 2006 Channel 4 TV programme The Root of All Evil? makes clear (Dawkins himself preferred the title The God Delusion which he later that year used for his book). Yet he would still be advised to concede individual freedom of belief on a personal, if not a political, level when deep questions of the meaning and ultimate nature of life are concerned, and this does not come across in his book.

Professor Dawkins has already responded to this last point in his Preface to the paperback edition (p.15):

“If only such subtle, nuanced religion [as that of sophisticated theologians like Tillich or Bonhoeffer] predominated, the world would surely be a better place, and I would have written a different book. The melancholy truth is that this kind of understated, decent, revisionist religion is numerically negligible. To the vast majority of believers around the world, religion all too closely resembles what you hear from the likes of [Pat] Robertson, [Jerry] Falwell or [Ted] Haggard, Osama bin Laden or the Ayatollah Khomeini. These are not straw men, they are all too influential, and everybody in the modern world has to deal with them.”

“numerically negligible”? Or has Dawkins been misled by the high public profile of the people he names into believing that they are more representative of the “vast majority of believers” outside the trouble spots of the American Bible belt and the Middle East than they really are?

Dawkins’s policy of focusing only on full-blown religious intolerance and full-blown atheism strikes me as counter-productive. It is just such polarisation which makes reasonable compromise impossible. His evolutionary principles should have told him that if he wants to see a decline in religiously motivated extremism, that Mount Improbable should also be climbed by small, gradual stages, rather than in one great leap from faith to atheism.

References

Konrad Szocik, “Religion in a future Mars colony?”, Spaceflight, March 2017, p.92-97. The author is based at the University of Information Technology and Management, Rzeszow, Poland.

Responses to Szocik’s article appeared on the correspondence page of Spaceflight, June 2017, p.230-231. In addition to an e-mailed letter by myself, the others were written by Peter Davey, James Royse Murphy, James Fradgley, and Keith Gottschalk.

Richard Dawkins, The God Delusion (2006; 10th anniversary edition, Black Swan, 2016).

C.S. Lewis, Till We Have Faces: A Myth Retold (Geoffrey Bles, 1956; Fount Paperbacks, 1978).

Please send in comments by e-mail.

Interesting and relevant comments may be added to this page.

| Site home | Chronological index | About AE |