= ASTRONAUTICAL EVOLUTION =

Issue 161, 24 October 2021 – 52nd Apollo Anniversary Year

| Site home | Chronological index | Subject index | About AE |

This post is also available on Wordpress

Black Arrow and Prospero – Fifty Years On

I wrote the following account for the German spaceflight magazine Raumfahrt Concret (due to appear in German translation in issue 119). It has not appeared in print in English.

On 28 October 1971 the UK became the sixth country to place a satellite into orbit with its own national rocket, following the USSR (1957), the USA (1958), France (1965), Japan (1970) and China (1970). Yet the British story was unique, for its satellite, Prospero, was only launched on the Black Arrow rocket three months after the Minister for Aerospace had stood up in the House of Commons to announce that the programme was being cancelled. Even today, fifty years later, the UK has not regained its ability to reach orbit, either as an individual nation, or, like France, as a leading member of an international consortium.

The story begins, as it did for the Soviets and the Americans, with a military rocket designed to deliver a nuclear bomb if the Cold War between East and West ever became hot. The British rocket was named Blue Streak. Its engines were built from an American pattern by Rolls-Royce – a company synonymous with the best of British engineering in motor vehicles and air transport, and the fuselage by de Havilland – the company responsible for the world’s first passenger jet aircraft, the Comet.

But from the outset Blue Streak had a fatal vulnerability: before launch it needed to be fuelled with kerosene and liquid oxygen, and this could not be done in the limited time that would follow warning of an attack. Any Soviet first strike would hit missile bases in eastern England before Blue Streak would have had time to soar out of its silos in retaliation. In the world of the four-minute warning, it was already obsolete. Rather than start again with solid fuel as the Americans did with Polaris and Minuteman, or with storable liquid fuels like the Titan (aerozine 50 and dinitrogen tetroxide), the British government decided in April 1960 to cancel the project in favour of purchasing the Skybolt air-launched missile from America, and, when that ran into problems, eventually opted to build four ballistic missile submarines and equip each of them with sixteen Polaris rockets, again bought in from the Americans.

But while Blue Streak was still under development, the need arose for a smaller rocket in order to start testing re-entry bodies. Since Blue Streak would make a ballistic hop through space and then re-enter the atmosphere, the nuclear warhead needed to be brought down safely (or unsafely, if one was on the receiving end) to its detonation point close to the ground, and in addition the designers needed to know what sort of radar signature it might produce as it did so. The solution was Black Knight: a suborbital rocket which proved to be so useful that it continued in service testing materials and re-entry capsules even after the demise of Blue Streak.

Black Knight benefited from the German work on hydrogen peroxide, which the British seized at the end of the war as their share of the legacy from von Braun’s Peenemünde rocket team. Hydrogen peroxide – water with one additional oxygen atom in each molecule – has the advantage as an oxidiser that passing it over a catalyst sets free the spare oxygen with enough energy to turn the plain water left behind into superheated steam. When one adds kerosene fuel, the mixture is hot enough to begin combustion with no need for a pyrotechnic igniter, simplifying the engine as well as removing the need to store cryogenic liquid oxygen. Another advantage is that the decomposing peroxide is energetic enough by itself to drive the pumps before going into the combustion chamber.

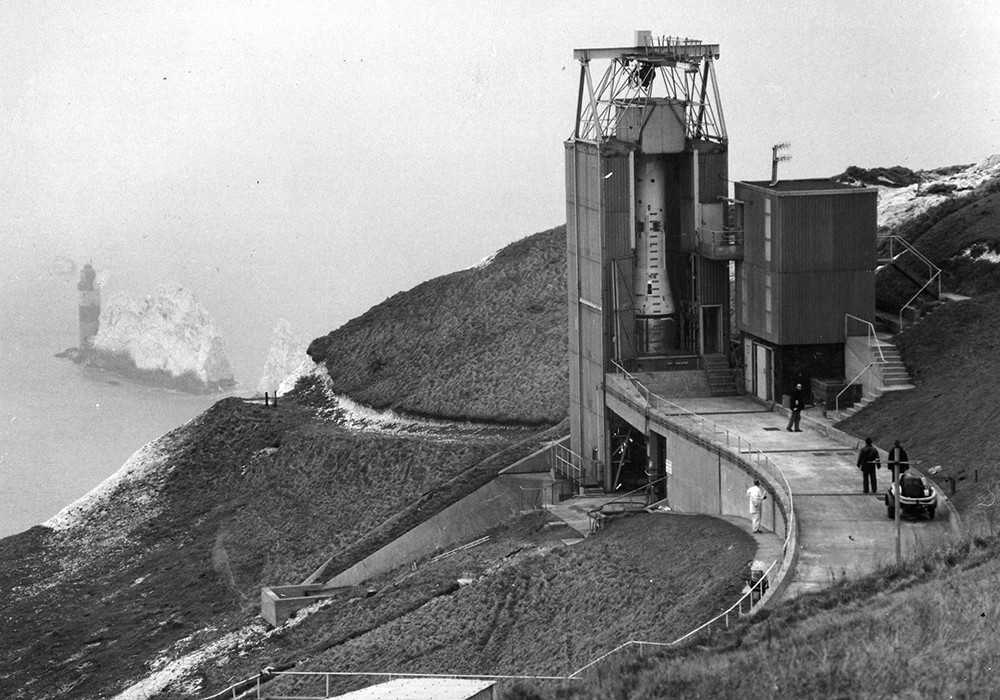

While Black Knight could not itself reach orbit, the Royal Aircraft Establishment calculated that a multi-stage stretched version could manage to do so with a small payload. This was called Black Arrow – another of the deliberately random Rainbow Codes (colour plus noun) used at the time to conceal the purpose of a military project. Its first and second stages would be based on Black Knight, with eight Bristol Siddeley Gamma engines in the first stage and two in the second. A solid fuel Waxwing kick stage would be added on top to provide that last little bit of speed necessary to stay up in orbit. It would be developed and manufactured by Saunders-Roe, a company which had previously manufactured flying-boats and the first hovercraft, and which had become part of Westland in 1964, a company better known today for its helicopters.

Black Arrow began life as a pet project of the Conservative Minister of Aviation, Julian Amery, supported by his civil service officials. Starting in 1963, Amery promoted it as a valuable research programme which would preserve and build on the legacy of Black Knight. But he experienced resistance from the Treasury, who regarded it as a mere prestige project and a waste of money. Amery bypassed approval from the Treasury and from Cabinet to announce the project to the media at the Farnborough Airshow shortly before the 1964 general election, making the project a fait accompli.

Some in the press believed that Amery was hoping that Black Arrow would give his party a more futuristic vibe in the coming election, as well as cover up unfortunate memories of some recent technology scandals. But in the event the Conservatives lost, and Black Arrow was inherited by the incoming Labour government.

During this period, officials in the Ministry of Aviation were concerned to preserve both the launcher and the satellite technology programmes. They slipped into discussions the concept of a unified National Space Technology Programme in which both the launcher and the satellites were essential, complementary components. As a result of this rebranding, Black Arrow survived the Labour government’s insistence that big technology programmes should be able to demonstrate economic value. But the Treasury could still impose financial limits, and the Ministry was forced to reduce the ambitions of Black Arrow as its costs increased. The planned number of launches was reduced from three per year to one, and the flight test programme was cut back from five flights to three.

In the event, five rockets were finally built, numbered R0 to R4. After testing on the Isle of Wight, the first four were shipped out to the Woomera rocket range in the Australian outback by air (R4 was not flown, and is today preserved at the Science Museum in London). The test campaign went as follows:

- R0: suborbital test of first and second stages, 28 June 1969: a failure: the vehicle started to oscillate in roll as soon as it left the ground, and when it started tumbling wildly had to be blown up by the range safety officer.

- R1: suborbital test of first and second stages, 4 March 1970: a success.

- R2: first orbital attempt, 2 September 1970: a failure when the second stage shut down early and the intended satellite fell back to Earth in the Gulf of Carpentaria off the northern coast of Australia.

This was the state of play when officials at the Ministry of Aviation initiated a review by Lord Penney, who in November 1970 recommended cancellation. Several factors led to this conclusion. The failure of R2 had highlighted the foolishness of penny-pinching in a high-risk development programme – a constraint that was not about to change, since the Heath government had been elected on a promise to reduce government spending. Meanwhile responsibility for space in the new government was being transferred to the Department for Trade and Industry, which had never been intended to support industry with its own technology research.

But above all, a shift in attitudes was in progress: the case for a launcher was becoming detached from the case for satellite technology development.

The availability of America as a launch provider for British satellites seemed secure, and replacing that service with an indigenous launch vehicle was seen as a more expensive – and therefore wasteful – option. The Americans had already helped with Britain’s first satellite, Ariel 1, which had been launched in April 1962 on a Thor-Delta rocket. Five more launches of these scientific research satellites followed, using the US Scout, and the programme was well under way, with the first three satellites safely in orbit, by the time Black Arrow came along.

Approaches to Europe had not borne fruit. As early as 1961 Britain had offered Blue Streak to the European Launcher Development Organisation as the first stage of its collaborative Europa-1 rocket, but had then seen a string of launch failures resulting from an inherently faulty management structure, and in 1968 had pulled out. While the Heath government would take Britain into the European Economic Community, the perception that collaboration on a European space launcher would make the nation more attractive as a European partner gradually fell by the wayside.

Against this background, ministers and officials were now coming to see satellite development as not only a viable independent alternative to an interest in launcher development, but altogether a more promising direction of progress. Even while there was not yet a significant commercial market for them, satellites were of great interest to the Meteorological Office, the Post Office and the Ministry of Defence, as well as to universities. The Penney report’s conclusion was not so much that Britain should abandon the ability to launch satellites (though it was that), as that it should use limited resources to their best effect. Not enough was being spent on either the launcher or on satellite development; there was only enough money for one of these; and the research into satellite technology was more attractive. Based on this, the officials promoted a change in policy.

Ministers agreed. The following February, the House of Commons began a review of Britain’s involvement in space. It became clear that little enthusiasm for Black Arrow was left. There was no sense of purpose to the programme and no recognition that Britain had any vital interests in pursuing an independent space capability. There were more important priorities for limited government funds, such as expanding the university system.

Many saw this as evidence of national decline. British popular culture of the 1950s had assumed that Britain would live up to its world-leading imperial history and continue to be a top-ranking world power. Science fiction authors such as Capt. W.E. Johns and Hugh Walters (I remember reading novels such as Return to Mars and The Domes of Pico when I was a child) naturally wrote of a future which would see British astronauts achieving no less than their American and Soviet counterparts, together of course with Dan Dare from the Eagle comics series. The late 1940s even saw British initiatives to build the world’s first supersonic aircraft (the Miles M.52: ordered by the Air Ministry in 1943, cancelled in 1946) and to launch the first astronaut on a suborbital spaceflight (the Megaroc: a stretched German V2 proposed by R.A. Smith and H.E. Ross to the Ministry of Supply in 1946, but rejected). But Britain was on its knees following the immense strain of fighting the Second World War, its empire was being broken up, the sense of belief in its greatness was fading, and there was no money available for prestige projects aiming at a visionary future.

Even as late as 1952, Duncan Sandys, the Minister of Supply, welcoming the entry into service of the de Havilland Comet, could announce that Britain must grasp the opportunity of developing aircraft manufacture as one of its main export industries in order to protect its future as a great nation. Twenty years later there was no such ambition, nor was there any vision of the strategic or economic importance of Earth orbit. Teams developing distinctively British concepts such as British Aircraft Corporation’s triple-spaceplane launcher, MUSTARD, in the 1960s, or the Rolls-Royce/British Aerospace HOTOL in the 1980s, were unable to raise enough official interest to progress beyond the early design phase (though HOTOL lived on with the help of private investors as the radically redesigned SKYLON, which has found a niche market in heat exchanger technology and advanced aero-engines, and may yet one day lead to a flight vehicle). Another twenty years on, the same lack of enthusiasm and the same penny-pinching attitude would dog Beagle 2, as well as making any follow-up attempt at a British Mars probe to complete Beagle 2’s mission a non-starter – this in a country that espoused an official space strategy one of whose main tenets was excellence in planetary science.

So it came about that in July 1971, Frederick Corfield, the Minister for Trade and Industry, announced the cancellation of the Black Arrow programme. Yet rocket number R3 was already in Australia and the team were fired up with enthusiasm for the one last launch that they hoped would prove that their system really worked. Permission was given to proceed.

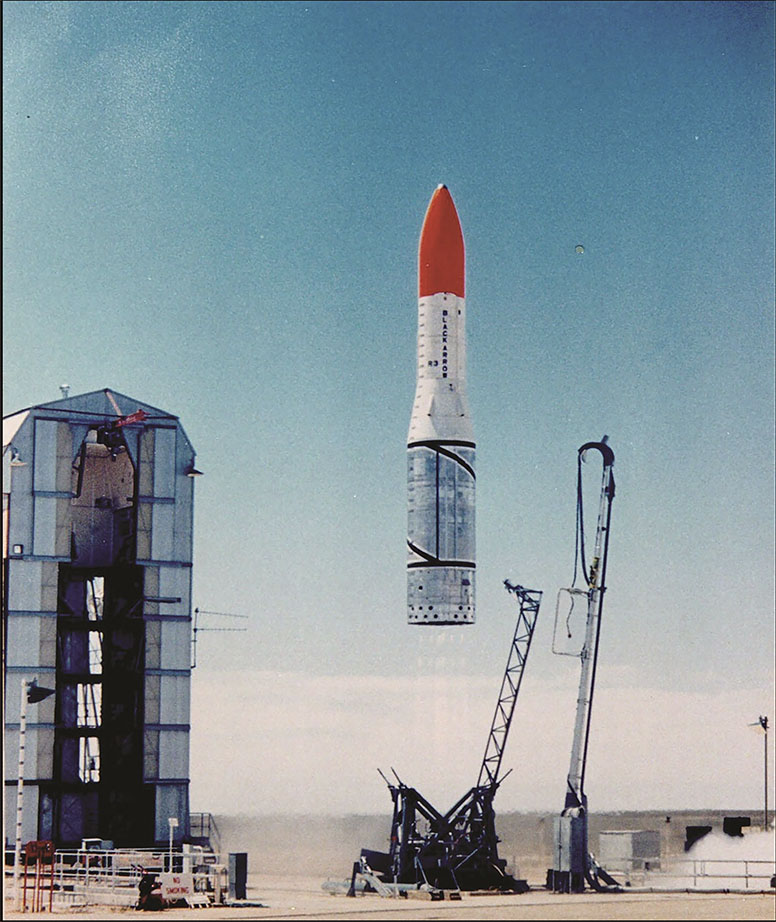

Following the Shakespearean theme established by Ariel, the satellite was named Prospero after the magician of The Tempest who bewitches the king and court of Naples but then finally gives up his power. The first launch attempt was scrubbed due to high wind speeds, but the next day dawned fine, and at 9 minutes past 1 o’clock in the afternoon, local time, the funny looking rocket with its bright red nose and a rakishly angled stripe around the first stage ascended from the launch pad on an almost invisible column of superheated steam and carbon dioxide.

Six and a half minutes later, Prospero bumped gently against the Waxwing third stage and was released safely into a near-polar orbit. And there it remains to this day, its initial altitude being high enough (534 × 1314 km) that it is not expected to fall back to Earth until around 2070, almost a century after its launch. Though it was officially deactivated in 1996, it was still possible to contact Prospero years later.

And there British achievements in launch vehicles remain, too, though happily not for much longer. While the Skylon spaceplane project has proved so far to be more ambitious than anything that governments or investors have been willing to commit to, two other private companies have been making better progress. By taking advantage of developments in technology and the great expansion in the market for small satellites, they are now very close, not only to launching into orbit with British-built hardware, but doing so from British – or specifically Scottish – territory:

- The British-Danish company Orbex, founded in 2015, is developing a launch vehicle, called Prime, to carry 150 kg of payload to polar orbit from Sutherland on the north coast of Scotland. The rocket boasts the world’s largest 3D-printed rocket engine, and burns the innovative propellant combination of propane and liquid oxygen. The first orbital launch is planned for 2022.

- The British-Ukrainian company Skyrora, founded 2017 and headquartered in Edinburgh, is developing a three-stage rocket, the Skyrora XL, with a payload capacity of about 300 kg, again to polar orbit. It uses basically the same propellants as Black Arrow, though the fuel is manufactured from waste plastic, and in this ecologically friendly form is known as ecosene rather than kerosene. The innovative third stage doubles as an orbital transfer vehicle in order to move satellites from one orbit to another and deorbit them at the end of their lifetime. The first orbital launch is due in 2023, from an unspecified UK site, but apparently still in the Scottish highlands, where the company has already been testing suborbital rockets.

These are in addition to the plans by the American companies Lockheed Martin and ABL Space Systems to begin launches of small satellites from the Shetland Space Centre in 2022, and by the US-based Virgin Orbit to use its air-launch system out of Newquay in Cornwall, following the 2018 announcement by the UK Space Agency that it was encouraging orbital launches from UK territory.

While the UK has clearly retired as a great power, and its days as a global leader in transport technologies are over, it is still possible for forward-looking British companies to find a niche market where their innovation makes a difference. In that sense alone, the legacy of Black Arrow and Prospero lives on into the 21st century.

Further reading

Francis Spufford, Backroom Boys: The Secret Return of the British Boffin (Faber and Faber, 2003), ch.1.

Stuart A. Butler, “National prestige and in(ter)dependence: British space research policy 1959-73” (D.Phil. thesis, University of Manchester, 2016).

Space Chronicle, October 2021 issue, published by the British Interplanetary Society.

| Site home | Chronological index | About AE |